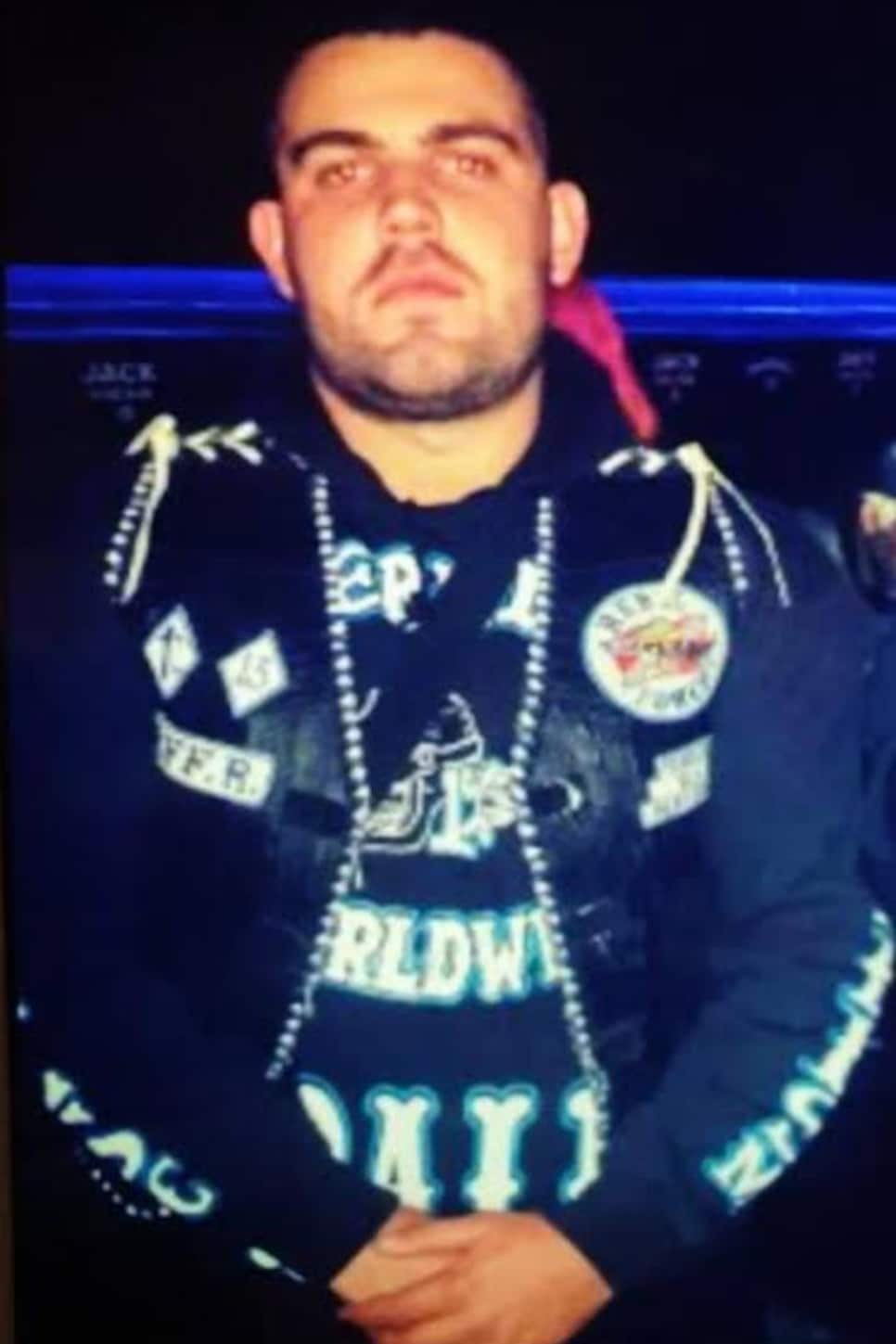

A SECOND CHANCE: Former gang member Peake served five years in prison for assault.

WREN STEINER

‘It’s a tough life, being a bikie. I think they saw an opportunity for one of their own to better themselves.’

SAFE SPACE: Peake learned the game at Lakelands C.C. in Perth, Australia.

WREN STEINER

FORMER PHENOM: At age 17, Peake was competing on national stages.

WREN STEINER

Says Peake while part of the Rebels: “I didn’t know how to be a person. The only way I can explain it is, I felt like everyone was a sheep and I was a lion.”

WORKING ON STABILITY: Peake cashed $335,000 NZD for his win at the 2025 New Zealand Open.

WREN STEINER

Video Player is loading.

Watch Now – This Callaway 3-Wood Can Help You Hit Driver-esque Bombs